|

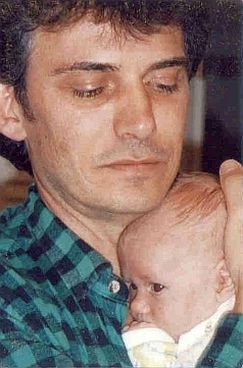

When my parenthood began, in spite of what I expected it to be, in spite of what I looked forward to it being, in spite of what I hoped it would be, regardless of whatever the right way to parent may be, no matter how much instinct I may or may not have to raise children, I discovered parenthood is really an ongoing experience of being as unprepared as it's possible to be for anything. Parenthood is ongoing proof I don't have all the answers. It's the continuing confront I know nothing. Parenthood is the unavoidable evidence over and over and over again that doing what I already know doesn't guarantee success.

There's no dress rehearsal for parenthood either. Once it starts, it starts. By the time I've learned how to do it right, the skills I've acquired are no longer applicable. Learning to parent is like taking aim at a moving target: it's never where it once was, and just as soon as I've locked my aim on to where it is, it's moved on, grown, morphed into something else, again requiring completely new skills.

To be sure, there's a certain amount of the machinery into which is already built enough nurturing mechanisms to almost get parenting right by default. Even the lactation reflex is automatic. That's parenting: an essentially human activity about which I know nothing, for which I'm totally unprepared having no learned skills, which is dictatorial and completely on automatic. Where, then, is the possibility of bringing transformation to it?

For me, examining what it takes to bring transformation to parenting first requires honoring all the not knowing about parenting and all the automaticity of parenting like a foundation.

It's extremely hard to do at times. All the protection machinery, all the survival machinery, while noble and decent seem so in the way of transformation, a created, intentional, non-linear verbal act.